Citrus 柑橘系

Japan's citrus farmers, cooks, and craft food makers are renewing citrus’ role as one of Japan's most important foods and seasonings by introducing new types of fruit, expanding citrus’ use in cooking and eating, and creating a seemingly endless array of delicious and ingenious citrus-based food products.

The Japanese archipelago is an island paradise of citrus, and the country is blessed with one of the most diverse, exotic, and extensive ranges of citrus in the world. Citrus trees are located almost everywhere, perfuming the air with their delicately fragrant flowers and decorating the landscape with their colorful round fruit and shiny evergreen leaves. They can be found on small family farms tiered on ancient stone terraces lining mountainsides and tucked deep within protected mountain valleys, in the courtyard gardens of urban residences and the backyards of suburban homes, and growing wild along the roadside. While the prime growing region is the temperate area of Japan's ancient heartland around the Seto Inland Sea, citrus flourishes as far north as Tokyo due to the country's excellent growing conditions, expert attentions of its orchard farmers, and unusually cold hardy varieties that have evolved in the country over millennia.

In addition to the beauty that citrus trees add to Japan’s landscape, its fruit, called kankitsukei, is a mainstay of the country’s natural, healthy diet and an essential seasoning in its light, clean-tasting cuisine and has been for centuries. Refreshingly delicious, loaded with vitamins and flavonoids, and naturally practical because of its easy-to-peel skin, citrus is the most popular fruit in Japan. Over 90% of the country's sweet-sour citrus is eaten as whole fresh fruit rather than being turned into juice or processed in other ways as is the case in most other countries. This has been true since ancient times when citrus was simply a handy source of fresh, beneficial, and tasty water. The difference today is that citrus farmers have evolved the country's edible citrus to be beautiful, juicy, and highly-refined combinations of rich sweet-sour flavor, making them as much luscious natural desserts as they are healthy portable snacks.

The citric acid of the country’s native tart citrus, in turn, is one of the country’s most important seasonings. After salt, acid is the second most important seasoning in the Japanese pantry. Like salt, acid refreshes food, restoring its life and brightening its flavor. And while salt increases food’s flavor, acid balances it and also harmonizes flavors in a dish. Lastly, different types of acid can add their own notes of flavor.

Citrus has traditionally been Japan’s main form of acidic seasoning because the country’s tart native citrus have a relatively mild, soft-tasting acidity that is well-suited to the country’s light foods and style of cooking, in addition to being beautiful, fragrant, natural, and widely available. (The juice of Japan's sour ume plum and shibu-gaki persimmon are other natural acidic seasonings.) Raw sashimi and cooked fish, nuts, mushrooms, and vegetables were all seasoned with citrus and/or salt. Citrus juice has also been traditionally added to soups and stews. For richer foods, more complex flavors, and different types of uses, a variety of umami-laden, blended condiments using two of Japan’s oldest and most unique citrus—yuzu and sansho—were created. These include ponzu (traditionally a savory-sour watery mix of fermented dashi stock, konbu seaweed, and yuzu juice), yuzu miso and kinome miso (salty-sour pastes that blend miso with either yuzu peel or sansho leaves, called kinome), and yuzu kosho (a spicy-sour paste made by fermenting yuzu peel, salt, and chili pepper together).

Citrus’ role in Japan’s cuisine is experiencing an exciting renewal due to the culinary revolution underway in the countryside. Citrus farmers, many of whom have moved from Japan’s big cities to start new slow lives in rural areas, have taken over family orchards or revived abandoned ones and are growing better quality fruit through organic farming practices as well as cultivating exciting new types of edible sweet-sour and tart seasoning citrus. They and other local residents are also behind an explosion of artisanal citrus-based food products. Aided by government subsidies to foster jobs and innovation in the countryside, these craft food makers are creating myriad variations of classical and new types of citrus-based seasonings, condiments, and sweet confections working at home, in the kitchens of local schools, and at small workshops in Japan's villages and country towns. Their efforts are supported by the trends of lighter, healthier seasoning and farm-to-table cooking and eating that are taking place across Japan. Cooks and eaters are once again squeezing fresh local native citrus on sashimi and also sushi and creatively extending citrus’ use to all kinds of foods and dishes. They are also pairing citrus with its ancient seasoning companion of salt to create new dishes, such as shio-yuzu (salt-yuzu) ramen and shio-nabe, salty hot pots heavily infused with citrus juice.

Much of Japan's citrus are unique native varieties, and over the centuries, the varieties have proliferated due to the ease with which citrus naturally mutates and hybridizes. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the world's standardized crop citrus of oranges, lemons, limes, and grapefruits were added to the mix during the expansionary days of global trade. These fruit, in turn, mutated and hybridized with the local citrus, creating new types of fruit. The basket continues to be added to by regular discoveries of natural new varieties and commercial hybrids.

Today, Japan is a curio pantry of citrus, and the country's collection includes varieties from each of citrus' four ancient core groups: mandarin, pomelo, papeda, and citron. The fruit can be roughly divided into two types: (1) sweet varieties of citrus, commonly referred to as sweet-sour fruit, that is readily eaten as is and (2) tart, largely inedible citrus that is mainly used to season other foods. The sweet-sour readily edible fruit are sweet, juicy mandarins, known as mikan, that come in every possible size, shade of orange, and combination of sweet-sour flavor, and pomelos, which have crossed with the local papeda and mikan to create firm, fleshy, and tasty new types of edible fruit. The tart citrus includes Japan's world-famous yuzu and its equally unique relatives that are members of the papeda group of citrus—the oldest and most primitive of the world's four ancient core groups of citrus. Japan's tart seasoning citrus also includes the most famous descendant of the strange and rare citron group of citrus, the lemon. Very popular in Japan, lemons come in all shapes and sizes and ranges of sourness albeit there is a general preference for a milder, sweeter variety to match the country's light cuisine.

A showpiece of Japan's citrus collection that is in a category of its own is sansho, a type of seasoning citrus. It is a hypnotically aromatic, small berry that is so pungent it tastes more peppery than citrusy and generates a pleasant tingling sensation in the mouth when eaten. Given its primal characteristics and the fact that all citrus originated aeons ago as small edible berries, sansho may very well be a variety of primeval citrus isolated in Japan after the country separated from the Asian continent.

The months from September through May are citrus' long main season, and a great deal of the pleasure of spending time in Japan during these months is the constantly changing varieties of fresh citrus that are available to eat and cook with. A crescendo is reached in winter when there is some type of delectably new and different rich and juicy sweet-sour citrus to try nearly every week. But given Japan's wide range of types of citrus and the efforts by farmers to keep the calendar full, there is some type of fresh fruit available all year round.

Snacking on Sunshine

Sweet, juicy, vitamin-rich, and full of the beneficial flavonoids that produce its bright orange color, mikan accounts for over 80% of all of Japan’s citrus production. There are nearly a hundred different varieties of mikan in Japan and many islands have their own unique fruit. Traditionally a winter food that refreshed the spirit as well as the body with its warm sunny glow, mikan has become such a staple of the Japanese diet that citrus farmers have found ways to make it available all year round. Wase-mikan is a small, intensely-flavored mikan that was developed to mature in October-November, which is well before mikan’s normal season. Mikan are also frozen whole during winter and then sold in the summer by the bagfuls, often at train station kiosks, to be enjoyed as a refreshing iced snack. The production of hot house grown fruit, referred to as “house” in Japanese, has increased in recent years to fill in the gaps.

Japan’s other sweet-sour citrus includes pomelos and their natural mutations and hybrids. One of the most popular is the buntan, which naturally hybridized with yuzu ages ago and then mutated into the almost forty different large, deliciously sweet, and fragrant varieties available today.

To satisfy Japan’s love affair with mikan, citrus farmers are working in a number of ways to create new varieties. This includes cultivating mutations discovered in their orchards, reviving heirloom fruit, and hybridizing mikan with other fruit. The goal is to introduce tempting and tantalizing new sweet-sour flavor combinations, improve practicality—easy-to-peel, seedless, edible pith—given Japan’s preference of eating whole fresh fruit, and extend mikan's season. The current stars are dekopon, a very sweet and juicy cross between mikan, orange, and pomelo that is very easy to peel, and the rarer and more expensive setoka, an even sweeter, juicier complex hybrid of several different kinds of mikan and oranges that is completely seedless. At the other end of the flavor spectrum is heirloom sanbokan, one of the sourest types of mikan found anywhere, which ripens late in the season. Associated with the bracing diets of the samurai, sanbokan is currently being cultivated by farmers for broader distribution from a single legendary tree in the castle of the former feudal lord of Wakayama prefecture.

The holy grail, though, is to create a fruit that is as much a natural sweet confection as possible, mirroring, for example, the very popular dessert of a citrus filled with jelly made from its own juice. The recently developed beni-madonna achieves this. Available for only one month a year in December, it is a very soft sweet fruit with flesh that is more like jelly than pulp and a skin that literally slides off the fruit.

As a result of the boom in artisanal citrus food products, most of Japan's sweet-sour citrus can be found in some form of jelly, jam, marmalade, or candied peel, providing other fun and satisfying ways to sample and enjoy their many variations. There has also been a proliferation of bottled speciality juices, which is a welcome addition to the line-up. A particularly interesting and creative new development are the efforts by cooks and craft food makers to cross mikan over into the world of savory cooking and eating. Mikan segments are being roasted to accompany grilled meats and to be added to hearty winter soups, stews, and hot pots, called mikan nabe. The traditional tart citrus blended condiments are now also being made with mikan, including mikan ponzu, mikan miso, and mikan kosho.

Following is a list of some of the main types of edible sweet-sour citrus. Season indicates the time of year during which the fruit has fully matured and ripened on the tree and is at the peak of its flavor. Delicious, high quality fruit is available longer than that because citrus keeps well both on the tree and after being picked and stored. Location indicates the prefecture in which the best fruit is grown. Knowing this can help you during your trips in the countryside and also at which prefectural food shop, called antenna shops, in Tokyo and other big cities you are most likely to find the fruit and its related food products.

Amanatsu

Discovered in 1740, amanatsu is a large, sweet natural hybrid of Japan's native bitter orange, mikan, and pomelo. Also known as natsudaidai, or summer orange, it has a refreshing sweet-sour flavor and is enjoyed eaten in segments or used to make drinks, ice creams, and sherbets. A famous summer dessert is amanatsu jelly served in its own fragrant hollowed-out shell.

Season: May - June

Location: Shizuoka Prefecture

Banpeiyu

A type of pomelo of unknown origin, the somewhat comical-looking banpeiyu is one of the largest citrus in the world. It is very popular in Japan because of its fragrance, gentle juicy sweetness, and mild acidity. Its flesh is typically eaten in segments and its thick aromatic peel candied in sugar. Because of its fragrance, it can often be found floating in hot winter baths.

Season: February - March

Location: Kumamoto Prefecture

Beni-Madonna

Beni-Madonna is a recently developed mikan-orange hybrid that comes the closest to the ideal of what a sweet-sour citrus fruit should be. It is a medium-sized, bulbous-shaped fruit with skin and flesh that are infused with the variegated yellow, orange, and rosy hues of sunshine. The skin virtually slips off under your fingers to reveal luscious jelly-like flesh that is mildly sweet and gently tart.

Season: December

Location: Ehime Prefecture

Buntan

Buntan is a big juicy type of pomelo with pale yellow, glossy skin, firm, highly-textured flesh, and rich, round sweet honey-like flavor. The oldest and most popular pomelo in Japan, it has mutated into over 40 different varieties over the centuries, including hybridizing long ago with yuzu, which gave the fruit its attractive aroma. A delicious citrus, buntan is typically eaten in segments and is a great addition to salads, stir fries, and light seafood and chicken dishes.

Season: January - April

Location: Kochi Prefecture

Dekopon

Developed in 1972, dekopon is a hybrid that combines mikan, pomelo, and orange. The result is a large, juicy, seedless, very sweet fruit that comes in a thick leathery peel which is more like a sack than a skin (that comes off easily once you pull on the handy twist-open knob on top). It is essentially a natural, ready-to-eat dessert. Dekopon is also a popular citrus in sherbets, ice creams, and other sweet confections.

Season: March - April

Prime Locations: Ehime, Kumamoto & Hiroshima Prefectures

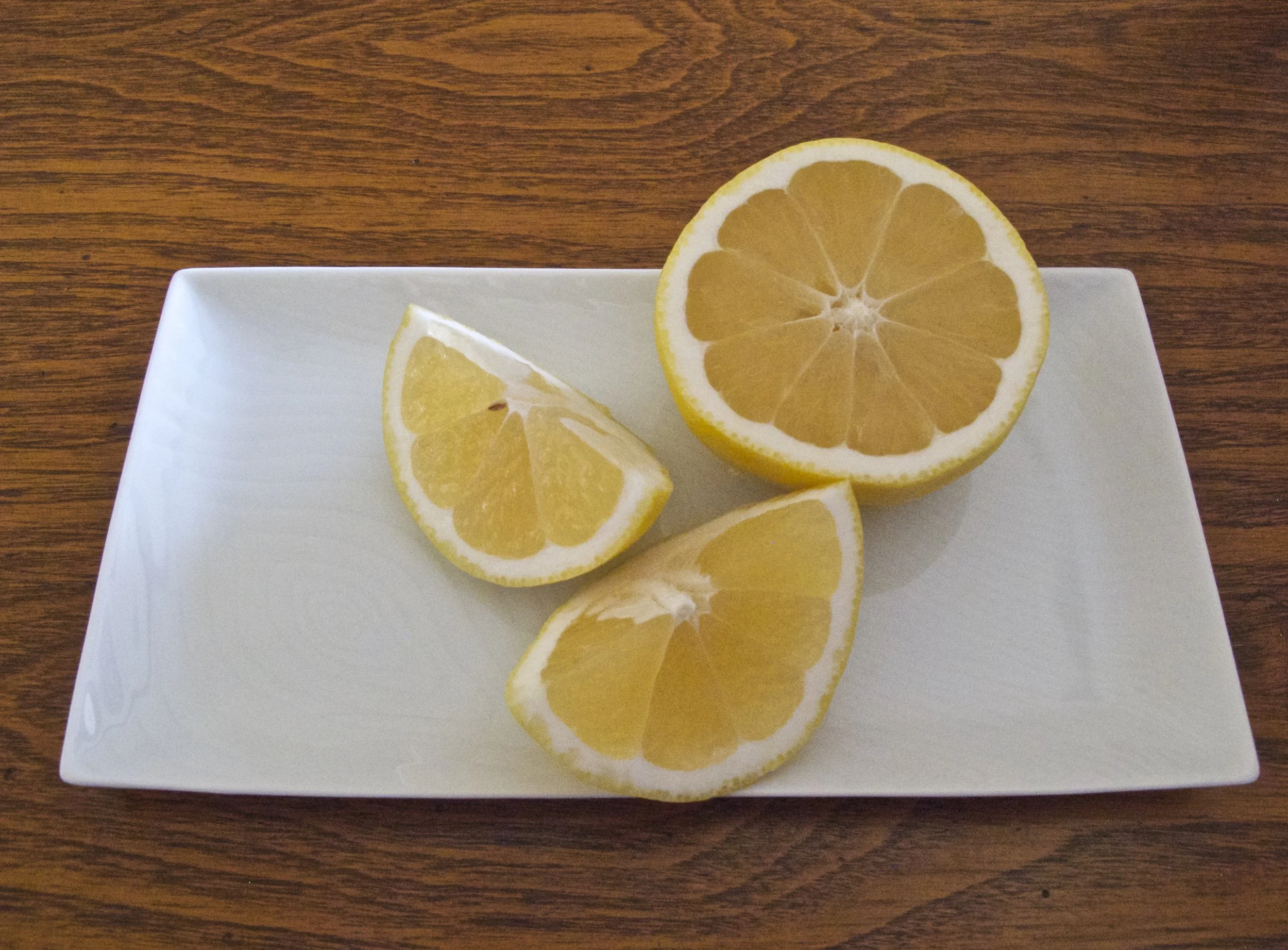

Haruka

A natural mutation of a hyuganatsu, which in turn is a natural hybrid of yuzu and pomelo, haruka is a bright yellow, round citrus with a protruding dimple at the end opposite of the stem—a characteristic of the yuzu family of citrus. It is a gentle, mildly sweet fruit with its own distinctive honey-like fragrance and flavor. It is eaten cut into pieces with bits of its sweet edible pith left on, which work well in salads.

Season: February - March

Prime Location: Ehime Prefecture

Hassaku

A natural hybrid between pomelo and orange of unknown origin found around 1860, hassaku is a large, orange-colored fleshy but not juicy fruit with a mildly tart and resinous flavor. It can be eaten either sliced up or with a spoon to avoid its bitter pith. It is one of the most widely cultivated citrus because its combination of sweet, sour, and bitter flavors make it a good base for jellies, jams, and marmalades and addition to fruit salads and desserts..

Season: December - March

Prime Location: Wakayama Prefecture

Hyuganatsu

A natural hybrid of yuzu and pomelo discovered in 1820, the large, vividly yellow hyuganatsu is a delicious and versatile fruit. Seductively fragrant and very juicy, it is eaten more like an apple or stone fruit than a citrus. The soft skin is peeled, leaving the thick edible pith and flesh intact, which is then cut into chunks so that the unusual sweetness of the white pith balances the refreshing sourness of the yellow flesh. The chunks are wonderful in salads and many kinds of savory and sweet dishes, and like yuzu, the hollowed-out shell can be used as a fragrant casing for sweet jellies or savory fillings.

Season: March - May

Prime Location: Miyazaki Prefecture

Iyokan

A natural hybrid discovered in 1886, iyokan is a large type of mikan. It is a very juicy fruit with a somewhat sticky sweet flavor. It is widely grown and is the second most popular type of mikan. Its segments come apart easily, making it a convenient snack and dessert fruit and also good in the kitchen, where it can be used in salads, savory glazes, and with pork, duck, and other game meats. Its thick but easy-to-peel, shiny, reddish-orange skin is very fragrant and delicious candied, and also attractive and useful in cookies, cakes, and marmalades.

Season: January - March

Prime Location: Ehime Prefecture

Kinkan

Known as kumquats abroad, kinkan are an ancient, cold-hardy, bite-sized citrus that combine a sweet-spicy peel with tart fruit inside. They are eaten whole like grapes for a refreshing chewy snack or as a candied dessert, with home cooks priding themselves on the secret recipes they use to bring out the luscious richness of the oil in the peel. Kinkan also work well whole in sweet-sour and other kinds of stir fried dishes and roasted before being chopped into relishes or added to hearty soups, stews, and braised-meat dishes.

Season: November - February

Prime Location: Miyazaki Prefecture

Mikan

One of Japan's oldest citrus, cold-hardy mikan are easy-to-peel, usually seedless, sweet, and juicy, and the country's most commonly eaten fruit. There is a large, ever increasing variety due to natural and commercial hybridization to enhance its flavor, perfect its peel-ability and seedless-ness, and extend its season. Some type of fresh mikan is available nearly all year round. Wase-mikan is a slightly tart mikan that matures early in Octo-Nov. Goku-wase-mikan is an even more refreshingly sour mikan that is ready to eat in Sept.-Oct. Increasingly mikan is being used in savory cooking.

Season: June - March

Prime Location: Seto Inland Sea Prefectures

Ponkan

A medium-sized hybrid between mikan and pomelo of unknown origin, ponkan is a natural improvement on the common mikan, being more fragrant, more refreshingly tart, and firmer in texture. Its skin is also easy to peel, which adds to its attractiveness as a daily snack fruit and dessert.

Season: January - March

Prime Location: Ehime Prefecture

Setoka

Setoka is a complex hybrid of several kinds of mikan and oranges developed in 2001. Large and seedless, it is one of Japan's sweetest, juiciest citrus. A beautiful smooth skin, fragrant aroma, and just the right touch of tartness make it lusciously decadent and refreshing. Although its thin skin is easily peeled, it is best cut and served because of the amount of juice that splashes out when opened. Its segments are great for decorating sweet confections.

Season: February - March

Prime Location: Ehime Prefecture

Seasoning with Kizu, or Tree Vinegar

Kizu, or tree vinegar, is a word used in Japan to describe the tart native citrus that is primarily used to season other foods. It is an apt description for the fruit's bright, clean, natural acidity and verdant, resinous flavors. Ranging in size, color, aroma, juiciness, tartness, and taste, they are handy squeeze balls of natural acidic seasoning that are used to season food with their fragrance, color, form, and texture as well as with their sourness and unique flavors. Just a few drops of citrus juice on sashimi not only enhances its flavor but also balances the aroma of the dish by countering the smell of the fish. Or a dish might be topped with some very thin slices of citrus to add pinwheels of color, fragrance, and chew (the citrus slices are expected to be eaten) in addition to harmonizing the food's flavor. Citrus’ color and fragrance are particularly important attributes given the Japanese belief that one eats with one's eyes first and that aroma accounts for 80% of one's sense of taste. The preferred color for tart seasoning citrus to finish food at the table is green, the color of nature. When the fruit ripens to yellow, it is used mainly for its juice in cooking.

Most of Japan’s “kizu” citrus are related to the country's unique, ethereally-fragrant, and exotic yuzu and include sudachi, kabosu, yuko, jabara, and yuzu kichi. It is a unique citrus family, and it is a disservice to their specialness to describe their flavor characteristics by comparing them to lemons, limes, or grapefruits. In general, they have a mild tartness, which suits the soft Japanese palate and the lightness of Japanese cooking, and their fragrances and flavors range from slightly floral to woody, peppery, and spicy.

Maturing from early fall to winter depending on their variety, their tartness tends to increase as the season progresses. To a somehwat surprising degree, their acidity and flavor align to other foods that have the same season and are from the same region. For example, the bright, floral acidity of sudachi, which is in season from August to October, is a good match for the first rich yet still delicate foods of autumn such as clear soups, gingko nuts, matsutake mushrooms, and grilled sanma (Pacific saury) and other tender light fish. In the Seto Inland Sea area where sudachi is largely grown, its juice is used on practically everything given its affinity with the cuisine of the region. Similarly, the richer, peppery, more sour acidity of jabara, which matures in November and December, works well with heavier, late fall and winter soups, stews, and foods and also the rich mountain cuisine of its native Wakayama prefecture, which includes meats like duck, deer, and boar.

The affinity between flavor and season and type of food also applies to lemons, which are a fairly recent addition to the Japanese pantry. They were introduced from abroad in the past couple of hundred years and have a higher acidity and more pronounced flavor than most native Japanese citrus. Maturing from January through March, lemons are typically used with foreign dishes, especially fried foods, and to balance the flavor of the bitter-tasting foods of spring, especially wild mountain vegetables.

One of the most delightful and rewarding innovations by citrus farmers in the past couple of years is the ao-lemon, or green lemon. These are simply lemons picked in late summer and early fall (August to October) before they have ripened and are still green. Both their skin and juice have a lovely floral scent because their growth stage is closer to the time of the tree's flowering, and their tartness is stronger and more spicy because they have not yet had time to mature. In addition to creating an autumn lemon (regular lemons mature during the winter), citrus farmers have virtually produced a new Japanese fruit given how different the flavor characteristics of ao-lemon are compared to those of regular lemons and how well they match Japanese cuisine. They are good as cooking ingredients and seasoning and refreshing in sparkling drinks and cocktails.

Two of Japan’s oldest tart citrus, sansho and yuzu, are almost entirely about the power of their fragrances. Both the berries of sansho and its small, shiny green leaves (known as kinome) are used to perfume all kinds of food and dishes to give them a sense of deliciousness. Yuzu's bright yellow rind is cut into slivers or hollowed out to form small bowls to add a seductive fragrance to tofu, salads, pickles, soups, simmered dishes, sweets, and drinks. (Yuzu is the only native tart citrus deemed acceptable to be served yellow to give a sense of sunshine during winter.) An ancient farmhouse dish is yubeshi, which is the hollowed out shell of a yuzu that has been stuffed with miso, rice flour, sugar, and walnuts, then steamed and hung up to ferment for months until the outer citrus skin has melded into a fragrant translucent wrapper covering a ball of deeply rich and satisfying sweet-savory goodness.

To preserve the delicate nuances of flavor of Japan’s seasoning citrus, they are best used at the end of cooking and to finish foods. Exceptions are juicy, full-flavored kabosu and yuko, which can stand up to cooking. For long cooking and high heating, such as savory glazes, jams and marmalades, and desserts, it is best to incorporate some of the fruit's zest or peel to ensure that the fruit's flavor is maintained. Bits of green zest are also attractive in any dish, hot or cold, such as dressings for green and fruit salads, soups, and desserts.

There is a lot of experimentation, innovation, and playfulness underway in the use of Japan’s tart seasoning citrus, especially in the countryside where citrus is abundant and at farm-to-table type restaurants everywhere. Fresh, local citrus is replacing the ubiquitous and all-purpose soy sauce and lemon to create lighter flavors, season more seasonally, and layer and blend seasonings to cook better and create new dishes. Japan's tart citrus is also being used on foreign dishes, such as pastas, cream soups, thick stews, and spicy curries as a healthy, local, plant-based acidic alternative or layering to the tang customarily provided by cheese, creme fraiche, sour cream, and yoghurt. The variations of classical blended citrus seasonings and creation of new ones seems endless. For example, ponzu can be found made from the juice of jabara, shikwasa, sudachi, et al., in addition to the old-time standards of daidai, kabosu, and yuzu. Some of the more interesting new citrus products are blends of sea salt and citrus like shio-ponzu, a mix of sea salt, lemon juice, and dashi stock, and shio-lemon, a fermented paste of sea salt and mashed lemons. Not surprisingly, there is also a wide variety of new citrus-flavored sake and other types of liquors, including Japan's first domestically made gin, which is flavored with yuzu and sansho. Lastly, each type of citrus is available in bottles of fresh, natural juice making it possible for cooks to use and experiment with the incredible variety of seasoning citrus all year round.

Following are the main types of tart seasoning citrus available in Japan. Season indicates the time of year during which the fruit has fully matured and ripened on the tree and is at the peak of its flavor. Delicious, high quality fruit is available longer than that because citrus keeps well both on the tree and after being picked and stored. Location indicates the prefecture in which the best fruit is grown. Knowing this can help you during your trips in the countryside and also at which prefectural food shop, called antenna shops, in Tokyo and other big cities you are most likely to find the fruit and its related food products.

Ao-lemon (Green Lemon)

Simply a lemon picked early but wonderfully different from a ripe fruit. It has a strong tartness, a spicy less specifically lemon flavor, and both its skin and juice express a delightful floral perfume-like fragrance. Because of these characteristics and its early start to the lemon season, its juice and charming green flecks of zest are used to season Japan's autumn foods and anything else a lemon might be used for, including sparkling drinks and cocktails.

Season: September - November

Prime Location: Hiroshima Prefecture

Ao-mikan

Sometimes called "baby" mikan, aomikan is a mikan that is picked early, before it is ripe, for its tart juice and attractive color combination of green skin and orange pulp. It is mostly used as a late summer and early fall garnish for sashimi, sushi, and grilled seafood and as a seasoning for soups, balancing their flavors and giving them a refreshing hint of tangy, faintly tangerine flavor.

Best Season: August - September

Prime Location: Seto Inland Sea Prefectures

Bergamot

A natural hybrid of bitter orange and lemon, bergamot grows all around the Seto Inland Sea area where it is known by a variety of names, including the Southern Yellow pictured here. It is a fragrant, juicy citrus with a kick of spice in its flavor that makes it very appealing and versatile in cooking. Its peel, juice, and segments are used in hot and cold drinks, salads and dressings, as a garnish for seafood and meat dishes or an ingredient in their marinades and glazes, and for jams, marmalades, and desserts. Softer and sweeter than other tart cooking citrus, its luscious spicy richness can also be enjoyed raw.

Season: November - January

Prime Location: Kochi Prefecture

Daidai

A native bitter orange with thick, highly aromatic skin and very sour juice, daidai is traditionally mixed with soy sauce to make a bright, salty-sour ponzu sauce that is added to winter hot pot stews and other braised dishes or as a condiment for anything when something more refreshing than soy sauce alone is desired. Its peel is used fresh as a flavoring when making pickles and dried in traditional medicines. The pulp is a great base for marmalades. Daidai is associated with New Year's and is the centerpiece of traditional decorations hung over doorways.

Season: November - January

Prime Location: Shizuoka Prefecture

Jabara

A rare citrus related to yuzu, jabara has a similarly unique and pronounced flavor profile and both its rind and tart juice are accented by its peppery fragrance and taste. Juicier than yuzu, it is a robust fruity citrus that goes well with meats and other rich foods and dishes. Jabara is also valued as a natural medicine for pollen allergies because of its high concentration of the flavonoid narirutin.

Season: December - February

Prime Location: Wakayama Prefecture

Kabosu

Another relative of yuzu, kabosu is a medium-sized fruit, and its plentiful juice and thick rind have a wonderful forest-like fragrance and woody flavor. One of the most versatile of Japan's native tart citrus, its rind and juice can be used to season all kinds of foods: fresh and cooked, light and rich, land and sea. Available in large bottles, kabosu juice is great to have in the kitchen for daily use.

Season: September - November

Prime Location: Oita Prefecture

Lemon

Coming to Japan from India by way of China centuries ago, lemons are commonly grown and used in Japan. They come in all shapes and sizes, and the most prized are the highly fragrant and mild, sweet-tasting lemons from the Seto Inland Sea area. Lemons are typically used as a garnish with richer, heavier foods like fried foods, grilled meats, and foreign dishes and as a flavoring for drinks and desserts.

Season: December - March

Prime Location: Hiroshima Prefecture

Sansho

One of Japan’s oldest, most unique citrus, sansho is used all year round to season food in a variety of ways. Its whole pungent berries are added fresh, or preserved in brine or dashi stock, to cooked dishes. The berries are also dried and ground up to be sprinkled as a tangy, aromatic spice over food. The small, shiny green leaves, called kinome, are used in cooking and also placed as a whole fresh sprig on a dish to garnish it with a fragrant, appetizing piece of the forest.

Season: All Year

Prime Location: Kyoto Prefecture

Shikwasa

Native to the islands of Okinawa, shikwasa is Japan's most tropical citrus. A small round green ball, its flavor profile changes over its long season, starting out sour and bitter and finishing slightly sweet and orangey. The color of its pulp also changes, going from green to orange. Shikwasa is the perfect counterpoint to Okinawa's spicy, meat-laden cuisine as well as its hot humid weather.

Season: August - December

Prime Location: Okinawa Prefecture

Sudachi

A small, perfectly round green fruit that turns pale-yellow as it ripens, sudachi has a bright taste and light floral fragrance. Being thin-skinned, its juice, not rind, is mainly used when a few drops of acid is needed to lighten and harmonize the flavors of sashimi, sushi, and grilled seafood, nuts and vegetables, and light soups and stews.

Season: August - October

Prime Location: Tokushima Prefecture

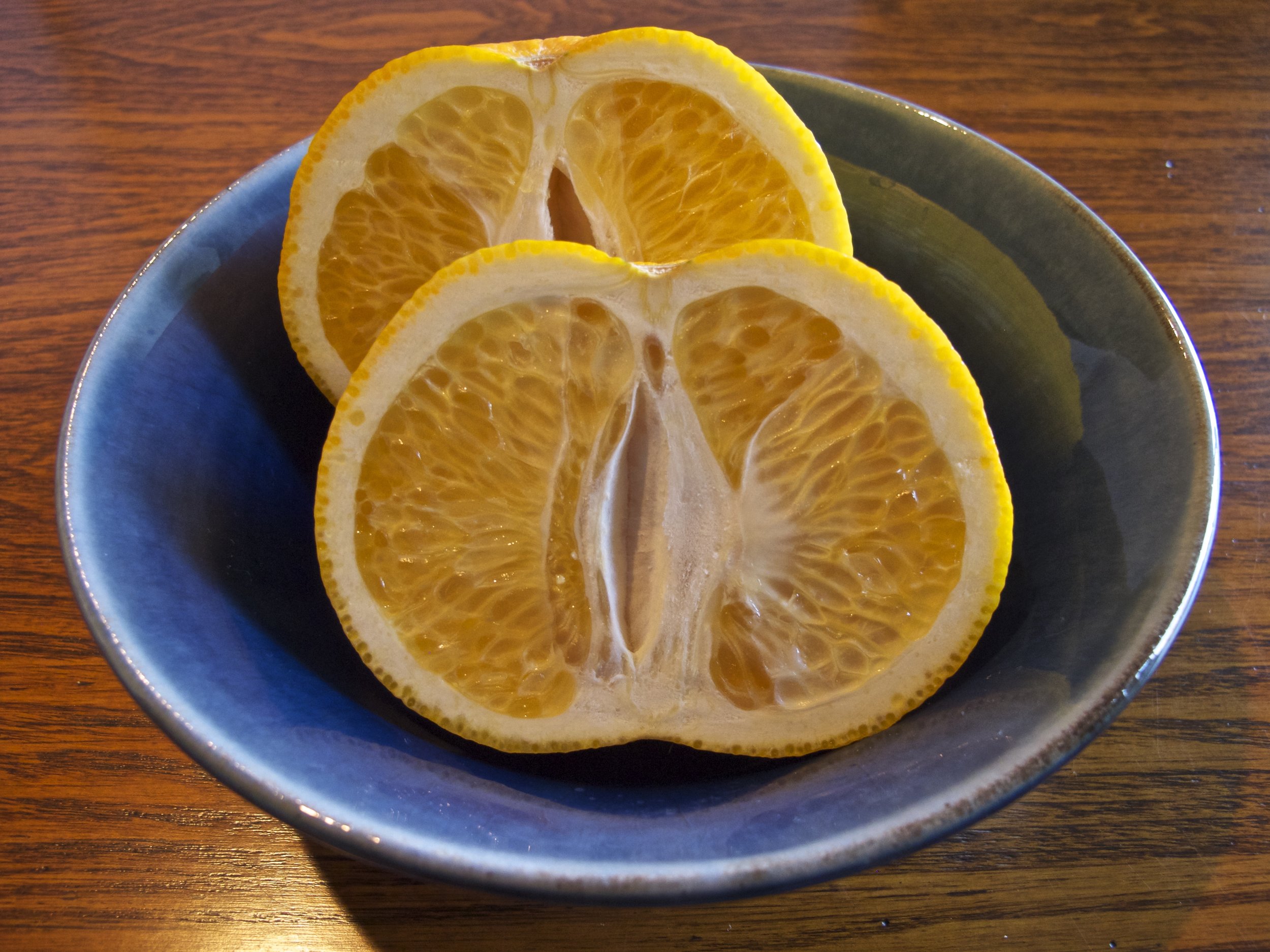

Yuko

Recently re-discovered after having been thought to be extinct, yuko is once again being cultivated for broad distribution. A small, yellow relative of yuzu, it is the sweetest of all types of tart citrus in the world, and has a rich, rounded floral-resinous flavor. It is excellent for making desserts, and its high level of acidity helps to thicken those made with milk and cream. It is also good for jams and marmalades (pictured).

Season: January - March

Prime Location: Nagasaki Prefecture

Yuzu

Cultivated for over 1,000 years and found across much of Japan, cold-hardy yuzu has a thick rind and little juice. Its strengths are its high acidity and rich, captivating fragrance that permeates both the peel and juice, which have been used for centuries to help preserve foods and add a seductive fragrance and refreshing flavor to all kinds of dishes: salads, pickles, soups, simmered dishes, sweets, and drinks. The whole fruit is also added to winter baths.

Season: November - December

Prime Location: Kochi Prefecture

Yuzu Kichi

A very sour and juicy, close relative of yuzu, yuzu kichi has its own unique, intensely spicy taste and fragrance. It can be thought of as a liquid spice as well as an acidic seasoning, and can be used to add heat to winter foods. One of yuzu kichi's attractions as a seasoning citrus is that it keeps its green color, unlike yuzu, which ripens to yellow.

Season: November - December

Prime Location: Kochi Prefecture

Story & Photos: Tom Schiller

A Citrus Paradise

While Japan's four seasons, warm days and cool nights, generous rainfall, nutrient-rich volcanic soil, and small family farms are excellent conditions for growing pretty much everything, the country’s climate, terrain, and traditions of its citrus orchard farmers are ideal for cultivating delicious, high quality citrus. The country's long hot wet summers ensure a deeply nourishing growing season. Its short winters are cold enough to ripen the fruit to its optimal size, color, and flavor yet mild enough not to kill the fruit or leave the tree dormant for too long. Japan's steep, folded mountains play an important role by providing the good drainage that is critically important to the health of citrus trees' shallow root system as well as protecting the orchards from too much wind. Citrus trees need good airflow but prefer a gentle breeze and their own chance to breathe that comes from proper pruning.

For centuries, Japan’s citrus farmers have built their hillside orchards on stone terraces called ishizumi, which provide significant benefits to the quality and flavor of the fruit in addition to enabling the farmers to better maintain their trees. Citrus trees need a deep but short soaking. Ishizumi capture and pool water, then quickly drain and recycle it down to the next tier, where it is pooled and drained again. Ishizumi also help by improving air circulation within the orchard, reflecting sunlight from their stones to the back and bottom of the trees, and generating warmth on cool nights from the heat retained in the stones. Ishizumi are such an important indicator of juicy, fully-flavored, small-farmed fruit that the word "ishizumi" is sometimes part of a citrus variety's brand name or at least listed on the label as being its orchard of origin. It is also becoming an increasingly meaningful differentiator as ishizumi disappear due to the high costs of maintaining them and the damage done to the stone walls caused by Japan’s out-of-control wild boar population.

Similar to many countries around the world, there is no clear standard in Japan as to what constitutes organic farming practices. In general, it can be safely assumed that most citrus fruit has not been highly chemically treated as the Japanese government only requires a minimum of pesticide spraying for fresh produce destined to be sold to consumers in stores. The bright, clear, consistent color and unblemished skin of these citrus is a sign they have been sprayed.

Still, there is an increasing number of small citrus farmers—who mainly sell their fruit locally at roadside stands and farmers markets—that offer a completely natural product which can have a superior flavor. By not spraying their fruit, farmers gain two flavor benefits. They do not coat their fruit with foul-tasting chemicals and they increase the fruit’s stress by exposing it to bugs and molds, which prompts the tree to respond in a way that heightens the richness of its fruit’s flavor. Some organic citrus farmers whose orchards are near the sea spray their orchards with diluted salty sea water to ward off pests and fungus. While this diminishes the stress-induced flavor benefits, it coats the tree with beneficial oceanic minerals. The skin imperfections of naturally-grown citrus are a small obstacle to overcome, and one can learn to appreciate their patinas as signs of character and natural beauty. They are also surprisingly easy to wash off.

Most of the best citrus in Japan comes from small-farm family orchards on the many small mountainous islands in the Seto Inland Sea and surrounding coastline of the big islands of Shikoku, Honshu, and Kyushu. The area is centrally positioned in Japan's sub-tropical region, and its hot-humid summers, mild winters, intermittent downpours, and lots and lots of sunshine—coming from the sky, bouncing off of the surrounding ocean, and reflecting from the stones of the ancient ishizumi that cover the landscape—produce the country’s greatest fruit. They have a rich, sweet flavor and beautifully bright, smooth, and glossy skin. Mikan and its treasured hybrids from Ehime prefecture, in the northwest corner of Shikoku Island, are especially delicious and of high quality, giving the prefecture the reputation as the citrus kingdom of Japan. Other leading producers in the area are Oita and Miyzaki prefectures to the west on Kyushu Island and Hiroshima prefecture to the north on Honshu Island. Hiroshima prefecture is considered the country’s lemon capital because of the juicy, slightly sweet variety grown there.

Delicious, high quality citrus—especially hardy mikan and yuzu—can also be found elsewhere in Japan. Orchards in the large producing areas of Wakayama and Shizuoka prefectures on Japan’s east coast benefit from the warm climate and mild sunny winters created by the Kuroshio Current flowing up from the southern Pacific Ocean. The Tsushima Current provides similar benefits to citrus farms on Japan’s west coast, and the folded nature of Japan's mountains creates sheltered valleys that foster good growing conditions in the country’s interior. In all of these areas look for citrus that comes from small family farms and orchards terraced by ishizumi.

Citrus fruit only matures and ripens on the tree. Once picked, its key flavor characteristics of aroma and flavor will not change. In other words, lemons will not become sweet nor will mikans become sweeter by sitting on a window sill in the sun. Over time, though, the fruit will decay off or on the tree, which typically includes changing color. One of citrus’ remarkable features is how slowly decay occurs because of the natural preservatives in its juice, and the fruit can remain in a suspended state of deliciousness for weeks and be serviceable even after months.

If you have a chance to pick your own fruit, keep in mind that orchard farmers believe that the fullest-flavored fruit comes from the top of the tree followed by those on the outside of the branches because they receive the most sunlight. And when eating the fruit, its best flavor comes from the stem end near the base of the flower.

Where To Buy

Citrus can be found all year round across the country at roadside stands, farmer's markets, fruit bins in supermarkets, and the fresh herb and spice sections of convenience stores.

In the Countryside

Citrus fruit are widely available in all of the prefectures in which they are grown. Michi no eki, which are marketplaces alongside main roads and in town centers that feature regional food, are where you will find the most complete range of local varieties of citrus as well as those that have been farmed organically. They will also have a large and interesting selection of food products made with local citrus.

Tokyo

Supermarkets: Japan's tart citrus used as seasonings, such as kabosu, sudachi, and yuzu, are sold alongside fresh herbs and spices in refrigerator cases in the vegetable section. Sweet edible citrus is typically in bins in the fruit section. Most supermarkets have a remarkably broad selection of Japan's many different varieties of citrus.

Prefecture Antenna Shops: In Tokyo, many prefectures have what are called “antenna” shops where you can buy pretty much everything you would find at a regional michi no eki—all kinds of food and drink, as well as traditional crafts and souvenirs. Most are conveniently located in the main shopping districts of Nihonbashi, Yurakucho, and Ginza. In 2016, for the first time, the Japan Center for Regional Development produced an English language map featuring the 15 largest antenna shops, which is available at most shops. For others, simply look up the location of the antenna shop by prefecture on the web to find the one that is home to the type of citrus you’re looking for.